Slavery in the Ozarks

By 1860, Missouri’s demographics had changed dramatically since its entry into the Union as a slave state in 1820. One hundred thousand Kentuckians settled in the central region of Missouri with fertile lands for cultivation and invaluable waterways for transporting products to southern markets, and the rapidly growing city of St. Louis. Many of these immigrants lived the ideal agrarian life of Jeffersonian political thought.1 They believed America should be a nation of farmers, and argued that a virtuous life on the land was the true destiny of America. The fertile soil of the region allowed for cash crops, especially hemp, to be cultivated. The combination of fertile soil and easy access to transportation made slavery profitable throughout the Missouri River Valley. Thus, for many of these western planters, slavery, in effect, was democracy.2 By 1860, 77 percent of Missouri’s 114,509 slaves resided along the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers, where the cash crops of the South were prevalent.3

Many of the settlers in Arkansas believed that slavery was an essential way of life. They saw the expansion of the federal government’s power as a threat to individual freedoms and property rights. Arkansas Democrats and Whigs alike lobbied in favor of slavery. The majority of the slave owners in Arkansas, however, resided in the state’s southeast corner, where cotton production boomed along the Mississippi River.4

A majority of the Ozarks’ emigrants were from Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia. They found the landscape similar to their native state. In contrast to the river regions of Missouri and Arkansas, the Ozarks had relatively few slaves. White farmers settled the region, working the land and building communities without chattel labor. While tobacco and cotton was grown in the Ozarks, the region’s lack of railroads or navigable rivers made it difficult to transport any mass produced traditional cash crops. Instead, farmers grew corn and other cereal grains for consumption.

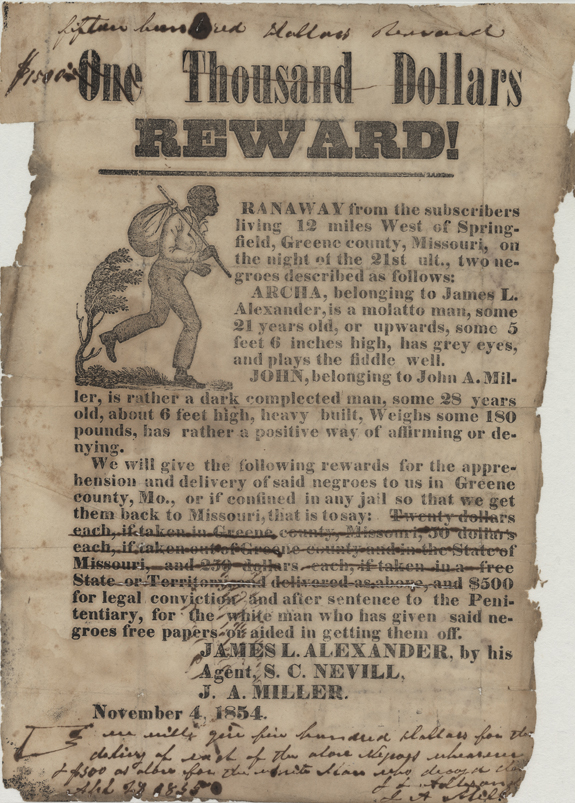

The Civil War brought may new challenges for slave-owners. As men left their homes and farms to enlist in the war, women took on new responsibilities. Beyond caring for the children, women suddenly were in charge of providing food for the family, cultivating the crops in the field, and ensuring the well-being and management of slaves. Bushwhackers and Jayhawkers would raid civilian property. Jayhawkers were notorious for liberating slaves and escorting them to Kansas. An 1863 slave schedule from Cass Township in Greene County, Missouri reports a staggering number of runaway slaves. Approximately one-third of the slave population in the township was reported as runaways.

The traditional conception of a slave owner, who lived on large plantations with multiple slaves, was not common in the Ozarks. In fact most owners worked along side their slaves to cultivate their crops. The Ozarks also contained Unionist slave-owners. Lucy M. Garrett, a Unionist in Greenfield, Missouri, exchanged her slaves for land in fear that they would be confiscated by Rebels. Several of the Native American tribes in Indian Territory were slave-owners. However, the Native American concept of slavery was not limited to those with African heritage. Several tribes enslaved Native Americans from other tribes.

In 1865, Missourians were leaders among slave states in the call for abolition of slavery within their borders. In the fall election of 1864, a majority of the voters declared in favor of a constitutional convention. On January 6, 1865, the Constitutional Convention assembled in St. Louis. On January 11, 1865, by a vote of 60 to 4, an amendment passed, which provided “hereinafter, in the state there shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except in punishment of crime, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted; and all persons held to service or labor as slaves are hereby declared free.” This amendment went into effect on the same day by proclamation of Governor Fletcher. Thus Missourians freed their slaves before the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.5

Black suffrage in Arkansas, however, was not granted until 1868. On March 2, 1867, Congress required each former Confederate state to hold a constitutional convention, write a constitution that included black suffrage, and ratify their constitution and the Fourteenth Amendment as prerequisites for readmission to the Union. In January 1868, delegates met in Little Rock. The convention gave African American males the right to vote, equality of all people before the law, forbade depriving any citizens of their rights based on race, and established a free public education system. With this new constitution and ratification of the Fourteen Amendment, Arkansas was officially readmitted to the Union on June 22, 1868.

Browse all collections in Slavery

Browse all collections in Slavery

- Christopher Phillips, Missouri’s Confederate: Claiborne Fox Jackson and the Creation of Southern Identity in the Border West (Columbia: University of Missouri, 2000), 28.

- Phillips, Missouri’s Confederate, 48.

- James Denny and John Bradbury, The Civil War’s First Blood: Missouri, 1854-1861, (Boonville, Missouri: Missouri Life, Inc., 2007), 3.

- Carl H. Moneyhon, The impact of the Civil War and Reconstruction in Arkansas (Baton Rouge and London: The Louisiana State University Press, 1994), 24.

- Earl J. Nelson, “Missouri Slavery, 1861-1865,” Missouri Historical Review, 28:4, pp.261-262.