Home Front

Image courtesy of the History Museum for Springfield-Greene County.…The condition of the people of Southwest Missouri is positively alarming, they being so destitute as to be in danger of starvation. Robbed repeatedly by the soldiers of both armies, their farms laid waste, their houses and fences burned, their horses and cattle driven off, and the male members of families absent in the contending armies, the situation of the women, children and old men, who remain, is most pitiable.1

The Ozarks of the Civil War saw thousands of men marching through on their way to battles in the Trans-Mississippi region. Yankees came through the Ozarks, and Rebels fought on Ozark soil and traveled to distant battlefield to defend their rights. This begs the question, of course, of what the home front of the Ozarks thought, felt, and believed about the Civil War. What did those men see, and experience, during their Ozark passage? What did Ozark women of the home front think and feel about living amid a War? What was the home front of the Civil War Ozarks like, and how did the War change it?

The Ozarks home front was one of hardship. Years of restrictive economic policies, from both the North and South, had propped up landed owners and industry barons at the expense of small farmers and tenant growers. The poor whites of the Ozarks were at a marked disadvantage in competing for sales of their goods, and were, for the most part, not prepared for the cessation in sales and market opportunities that the sectional crisis brought.

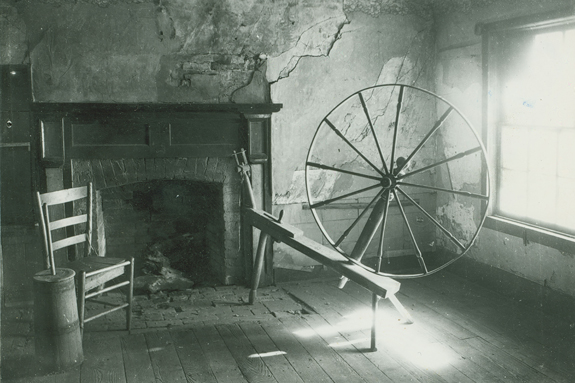

The rocky hills, poor soil, and tree covered topography coupled with weather vagrancy and long distance commutes to navigable rivers gave an Ozarks farmer limited commercial access for his goods. Thus, most families were as self sufficient as possible, producing their own cotton, wool, wheat, corn, oats, and tobacco for family use and consumption. Their household goods were often handcrafted, and their foodstuffs either home grown or acquired at one of the many small community grain mills. The cheap land that brought settlers to the area was still such that a town might be a day’s ride away. Small churches and the occasional school were the physical ties that bound communities together. Letters to far off family and friends was, in reflection, the only tangible and consistent link to the rest of the regional society.

Sustaining a livelihood in the spirit that it had been engaged was often quite difficult. Home keepers of the day wrote of droughts and insect infestations wreaking havoc on already spare crops, and several diarists of the Ozarks wrote with anger and frustration at the partisan violence affecting their grain supply, access to town goods, and mail delivery. When salt, necessity for curing meat in the age before refrigeration, became an impossible to find commodity (due to large military requirements) the civilian struggling on the home front were forces to improvise. In his travels through Northwest Arkansas and the Indian Territory, Dr. Rufus Gilpatrick saw women “digging up the dirt from smoke-house floors, and leaching it in a hopper, in the manner that soap is made by farmers, and afterward boiling the leachings in order to concentrate the salt it contains.”2 She could also dry as many wild fruits, such as persimmons and paw paws, as possible, enhancing their natural sugars to make up for the lack of refined sugar. Hundreds of shortcuts, substitutions and resourceful tactics were born of frontier hardship.

Wartime shortages further complicated what had become, by mid-War, a life of outright denial. With access to medical care severely limited, if not utterly unavailable, many Ozarks citizens suffered quietly and consistently with the rampages of disease that hit their already weakened immunities. The North had been afforded the strength of industrial output that far exceeded the Southern capacity for direct competition, and as the War encroached on Southern soil, the Rebels found their routes of commerce halted, their shipments blockaded, and their outside support dwindle. As planters in the South stayed afloat with commodity crops like tobacco and cotton, less food was grown to support an already deprived population. Thus, far more Southerners suffered malnutrition and starvation than did their Northern counterparts.3 It is through their diaries and letters that we learn how, in exemplary frontier fortitude, many carried on, despite disease and deprivation, and survived on sheer pluck and determination.

Politics of the day – staunchly partisan, defined by multiple parties with platforms based on single issues and wholly exclusionary of negotiation and compromise – must have left many Ozark citizens feeling utterly hopeless in the face of the ongoing War. Then, as now, representation was frustratingly inexact. Missourians suffered the unusual quandary of dual governments, after the secessionist-leaning Governor Claiborne Jackson was run out of the capitol in July, 1861 and replaced by the staunchly Unionist Hamilton Gamble. Jackson and his “rump” legislature took Missouri into the Confederacy that October, at his hastily convened convention in Neosho. His government operated out of Arkansas and Texas in exile, and those who supported him and his politics were sure to feel beleaguered, not only at the lack of consistent Confederate recognition, but the wavering support their cause found following Jackson’s death the next year. As military leaders swept into the Ozarks and mandated Union support from the tip of a drawn sword, many Ozarks homes were divided and destroyed.

Support for the Union or the Confederacy, as well as a stubborn belief in neutrality, could all be found across the Ozarks. Missouri, as a Border State, entered into the violence early in the War, with the battles of Carthage and Wilson’s Creek taking place within the first four months of the War. Army occupation waned for the next six to nine months, with the Union Army only permanently occupying Springfield, the largest city in Greene County and the surrounding Ozarks, in February 1862. While Kansas was adamantly for the Union, secession-minded Arkansas had areas of strong Unionism. Both regions employed a modicum of middle ground thought, if for no other reason than to quell the bloodshed that had already marred their communities in ongoing guerrilla violence.

A Civil War-era home keeper of the Ozarks would have read the newspaper regularly, perhaps out of St. Louis, Rolla, Springfield, or Carthage. By the winter of 1861-62 most of the secessionist-minded papers were shut down by occupying Union forces, and what “news” there was tended to be highly critical of the Confederacy. There was a very vocal opposition to the harsher Union policies, and newspaper editors of the day were not shy in lambasting the strong arm tactics of blundering military leaders and figurehead politicians. In many ways, the press formulated popular opinion on war, peace and politics just as their contemporaries still do.

By mid War, the home front of the Ozarks, and its apparent abandonment, had the attention of the Union Army and the Missouri State Militia, or MSM. The MSM was ordered early in the War to maintain peace in the occupied territories, be that through quelling guerrilla violence, ensuring Union loyalty through Rebel property seizure, or actively protecting homes and businesses from further depredation. To augment the MSM, the Enrolled Missouri Militia, or EMM, was formed in 1862. A compulsory force, all able bodies loyal Missouri men were required to register and were subject to muster, with duty primarily at strategic garrison points, to repel attacks, or, more commonly, to strengthen defenses by digging earthworks. With the huge numbers of soldiers present in and around Springfield, the commanders contemplated reducing their regiments in order to “resupply” the home front with men.

Most of the men in the EMM have families who are in destitute circumstances, having been plundered by both loyal and rebel armies…

It is absolutely necessary unless the country is abandoned by the citizens, that as much land as can be peaceably cultivated, should be planted, to enable their families to live and to supply in part at least the future necessities of the community and army.

By so reducing the Regiments more men could be relieved from active service and become producers…

Brig Gen Colley B. Holland Order to Col. William D. Wood, March 7, 1863

Ongoing violence, however, kept many men in their uniforms. The fighting age men that returned often did so briefly, as the demands for soldiers in the field too often outweighed the demands for protection and production at home. Myriad enticements kept some less patriotic men from serving their full time; the Confederacy, in particular, suffered huge numbers of deserters in the latter part of the War. In the Ozarks, following Sterling Price’s ill fated raid of 1864, the Rebels that entered Missouri scattered and went their own way as the raid moved north and west through the state, a colossal failure of conviction by the weary men under Price.

The home front of the Civil War remained markedly absent of a male figure, with most “fighting age” men either armed for the Union or the Confederacy, or operating under the cover of darkness as a partisan bandit. Those that held their homes together – young mothers with several children, or elderly women living with their extended families – were a tenacious and brave bunch. Facing violence, managing a home without a secure network of support, raising a family in the midst of disease and deprivation, tending to crops with a diminished workforce…all combined to make hardship an everyday reality.

Browse all collections in Home Front

Browse all collections in Home Front

- “From the St. Louis Republican.” Milwaukee Daily Sentinel, March 21 1863, page 2 column 2.

- “From the Far West.” New York Times, March 26, 1863, page 1 column 6.

- Varhola, Michael J. Everyday Life During the Civil War. (Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 1999), 80.