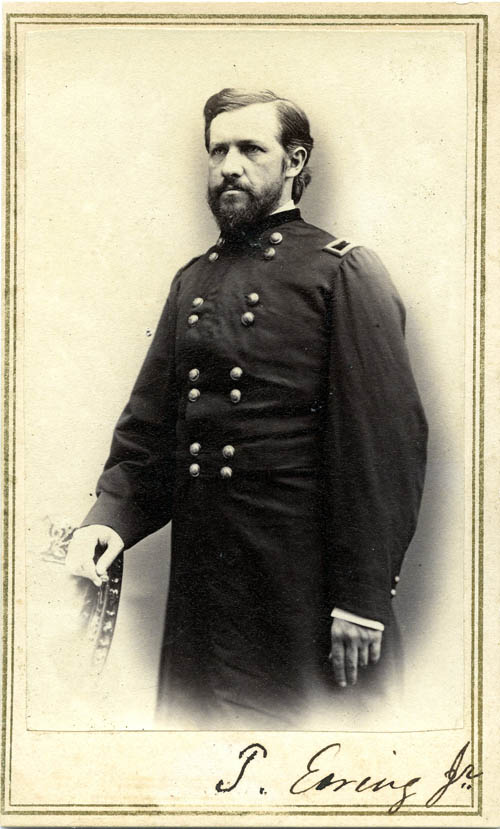

Ellen Cox Ewing Papers

Image courtesy of Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield

Ellen Cox Ewing was a native of Ohio and the wife of Union General Thomas Ewing, Jr. Thomas, was a lawyer before entering into military service for the United States Army. The Ewings moved to the Kansas Territory in 1856, settling in Leavenworth where Thomas Ewing practiced law with his brother Hugh and brother-in-law William Tecumseh Sherman.1 Ewing also took an active roll in the organization of the Kansas Republican Party. He could not identify himself, or Kansas, with the pro-Southern Democracy of Presidents Pierce and Buchanan, but worried that the radicals/abolitionists would take the Republicans down. Ewing served as a member of the Leavenworth Constitutional convention in 1858, and was elected Chief Justice of the State in 1861.2

Mrs. Ewing visited her family in Ohio in the summer of 1861. Upon her return to Leavenworth, Mrs. Ewing wrote her aunt and sister recalling the adventurous trip home. On the returning train to Leavenworth, she sat by “the notorious [Charles R.] Jennison, Captain of the ‘jay Hawkers’, with his family, He is a gentlemanly man, but a terror to the Missourians.”3 Charles R. Jennison was a doctor before joining the military, and a strong supporter of abolitionist John Brown. Kansas Governor Charles Robinson commissioned Jennison on September 4th, 1861 as lieutenant colonel of the 7th Kansas Cavalry, which became known as “Jennison’s Jayhawkers.” Jennison and the 7th Kansas Cavalry were assigned to the command of the western border of Missouri with headquarters at Kansas City. Jennison was determined to clear the border of guerrillas, and quickly adopted a “scorched earth” strategy of warfare against his Confederate enemy. He seized from the guerrilla-infested territory of western Missouri the materials needed to wage war and destroyed property he could not use.4 His military actions cause Jennison to become a household name along the Kansas / Missouri border. In, 1862 General David Hunter appointed him acting brigadier general, and he was placed in command of “all the troops in Kansas west of and on the Neosho.”5

Jennison’s reputation made passengers on the train fearful of an attack by Rebels or Bushwhackers who wanted to kill him. Ellen stated,

The Conductor told Tom that word had been sent to him that five hundred Secessionists had gone to Palmyra and that they intended killing him, the Engineers, the mail agent, and several others. Tom made me lie down upon a seat – and the children also. There were seventy Missouri Rifles on board with which the passengers armed themselves and got on top of the Cars ready for a fight. We passed about three hundred rebels in a woods, we saw their horses hitched to the trees, but they made no demonstration upon us, and we came through safely and pleasantly. For about an hour I thought perhaps I ought to have remained in Ohio.

Ellen Ewing Letter to Jinny and “Auntie.” Aug. 20, 1861

Mrs. Ewing’s husband, Thomas, resigned his judgeship in 1862 to recruit the 11th Kansas Volunteer Cavalry, which he was elected colonel. His regiment fought in the Battles of Fort Wayne, Cane Hill and Prairie Grove. For gallantry at Prairie Grove he was made brigadier-general, March 13, 1863. In the immediate wake of the Lawrence Massacre (i.e., Quantrill’s raid), Brigadier General Thomas Ewing, Jr., commanding the District of the Border, issued “Order No. 11” on August 25, 1863. The Order, aimed at those who supported the guerrilla fighters, commanded all residents living in the border counties of Bates, Jackson, Cass and the northern half of Vernon to vacate their homes. Those families were required to give oaths of loyalty to the Union, and their evacuation was demanded within two weeks. Ewing hoped depopulating these Missouri border countries would eliminate the safe havens support structure for guerrillas in the region.

While the border county populations dropped from 10,000 to 600, Order No. 11 failed to accomplish its professed purpose.6 Instead of driving the guerrillas out, the abandoned land became a sanctuary for bushwhackers. They no longer were required to steal from civilians, as they could simply forage through the deserted farms and homes for whatever supplies they needed. Coincidentally, after Order No. 11 was issued, no major guerrilla raids were conducted into Kansas from Missouri. However, it is extremely unlikely that the order was more than a minor and indirect factor in achieving this result. Of greater importance were the strengthened border defenses of Kansas following the Lawrence Massacre, an improved home guard system in that state, and above all the fact that the bushwhackers during the summer of 1864 concentrated their operation in Northern and Central Missouri so as to prepare the way for Sterling Price’s invasion that fall.7

Soon after the war’s end, Thomas Ewing moved to Washington, D.C. to practice law. The family then moved back to their native state of Ohio, where Thomas remained active in political affairs and served his native community as a Democratic representative to Congress (March 4, 1877-March 3, 1881).8 He subsequently moved to New York City where he died as a result of a streetcar accident on January 21, 1896.

Contributed by the Pearce Museum, Navarro College

- William E. Parrish, Biographical sketch of “Ewing, Thomas, Jr.” In American National Biography ( New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), http://www.territorialkansasonline.org/~imlskto/cgi-bin/index.php?SCREEN=bio_sketches/ewing_thomas

- Autobiography of Thomas Ewing, F. J. Heer Print Co., Columbus, Ohio 1912.

- Ellen Cox Ewing Letter to Jinny and “Auntie.” Aug. 20, 1861. Ewing (Ellen Cox) Papers, 1861, 2005.070, Pearce Civil War Collection, Navarro College, Corsicana, Texas.

- Stephen Z. Starr, Jennison’s Jayhawkers: A Civil War Cavalry Regiment and Its Commander (Baton Rouge, La.: Louisiana State University Press, 1973).

- William E. Connelley, A Standard History of Kansas and Kansans (Chicago: Lewis Publishing Company, 1997), http://skyways.lib.ks.us/genweb/archives/1918ks/bioj/jenniscr.html

- Albert Castel, “Order No. 11 and the Civil War on the Border” in Winning and Losing in the Civil War, (University of South Carolina Press, 1996), http://www.civilwarstlouis.com/history2/castelorder11.htm.

- Albert Castel,”Order No. 11 and the Civil War on the Border” in Winning and Losing in the Civil War, (University of South Carolina Press, 1996), http://www.civilwarstlouis.com/history2/castelorder11.htm.

- Thomas Ewing, Jr., Papers, 1856-1908, Finding Aid and guide to microfilm collection, see: http://www.kshs.org/research/collections/documents/personalpapers/findingaids/ewing.htm