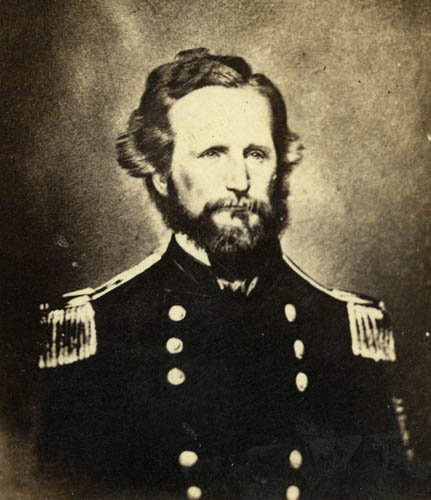

Nathaniel Lyon Papers

Image courtesy of Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield

Born on July 14, 1818 to Amasa and Kezia Lyon in Ashford Connecticut, Nathaniel Lyon learned from working on his family’s farm the importance of discipline and hard labor. Lyon was short in stature and of slender build. He had a long narrow face with course sandy hair and whiskers that were almost red, yet his strong character made up for whatever he lacked in physical appearance.1

Having been raised in such a regimented home it seemed only natural that he would join the military. Lyon attended the United States Military Academy and graduated 11th out of 52 in 1841.2 He was a skilled officers having fought in the Seminole and Mexican wars. During his service in Mexico, Lyon was exposed to slavery and wrote home describing the institution as, “the scourge & curse of humanity.”3 Lyon was eventually assigned to Fort Riley in Kansas, where he a strong Unionist as a result of the turmoil surrounding the violence along the Missouri Kansas Border. Lyon had been a Democrat, but the scenes of fraud and violence surrounding him in Kansas made him seek other political platforms. He published his opinions in a local newspaper called The Manhattan Express writing on November 23, 1861, “There seems to be little doubt that several of the Southern States will precipitate themselves into disaster and disgrace, if allowed to do so…Time must show: the only thing safe to predict is, that the conduct of the South must involve her people in suffering and shame.”4

Lyon was never afraid to speak his mind and it earned him a reputation among military and political leaders as someone who was “intolerant of opposition, unmindful of the many obligatory courtesies of life, easily aroused to a degree of anger that was almost insane in its manifestations.”5 Lyon was one of the most respected and feared generals in the army. He possessed a violent, hair trigger temper that got him a court-marshal for brutally beating and torturing an unruly enlisted man.6However, it was Lyon’s unwavering belief in the Federal government and its cause that made him a good leader and why he was selected to command the Union troops in Missouri.

In February 1861, Lyon was made commander of the Union arsenal in St. Louis, Missouri, where tensions grew between the Union soldiers stationed there and the secessionist governor of the state, Claiborne Jackson.7 When the Civil War began, Jackson refused to send volunteers from the state to aid Abraham Lincoln. Instead, Jackson had the militia muster outside the city to begin training. On May 10, 1861, Lyon and his troops surrounded the pro-Confederate Missouri militia under General D. M. Frost, and forced their surrender. Lyon’s actions regarding the Camp Jackson affair were highly controversial. Lyon could have administered the Oath of Allegiance to Frost’s men in the camp and simply issued Frost a writ of replevin through a federal marshal, but Lyon ignored these more peaceful methods and forcefully captured the camp and its inhabitants.8 Then, while marching his captured prisoners through St. Louis, many citizens began to riot, during which Federal troops to fire into the civilian crowd.9 Twenty-eight people were killed during the event and many others were wounded.

On May 17, 1861, Lyon was promoted to brigadier general and was given command of Union troops in Missouri. A month later, Lyon met with General Sterling Price and Governor Jackson at the Planters House in St. Louis to discuss the renewal of the Harney Agreement. After hours of debating, the frustrated Lyon rose to his feet and stated, “Rather than concede to the State of Missouri for one single instant the right to dictate to my Government in any matter however unimportant, I would see you, and you, and you and every man, woman and child in the State dead and buried…This means war.”10 Two days later, Lyon and his men marched to evacuated capitol and gained control of Jefferson City, forcing Governor Jackson and his men to retreat to Southwest Missouri. Now, Federal forces held control of Missouri’s two most important cities, St. Louis and Jefferson City. Lyon, and all the influences favorable to him, represented it as a great victory for the Federal arms, and it had a most depressing effect on the Southern Rights element. It compelled, too, the State forces to abandon the Missouri river, giving the Federals control of it from Kansas City to its mouth, and placed a formidable barrier in the way of recruits from the northern Missouri attempting to reach Price.11

Once in command of all Union troops in Missouri, Lyon began to pursue the capture of Governor Claiborne Jackson and the remaining Missouri State Guard. On August 10, 1861 the Union forces met a combined force of the Missouri State Guard and Confederate troops under the command of Ben McCulloch and Sterling Price near Springfield, Missouri, during the battle of Wilson’s Creek. Nathaniel Lyon was killed during the battle while trying to rally his outnumbered soldiers. Lyon was the first Union general to fall on the field of battle and the North’s first hero of the Civil War.12 Although the Confederate forces would win the Battle of Wilson’s Creek, Lyon’s efforts prevented the State of Missouri from joining the Confederacy and he would be forever remembered as the “Savior of Missouri.”

Contributed by Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield

- James Peckham, General Nathaniel Lyon and Missouri in 1861: A monograph of the Great Rebellion, New York: American News Company Publishers, 1866, pg 61.

- “Nathaniel Lyon”, Civil War Preservation Trust, 1156 15th Street NW, Suite 900Washington, D.C. 20005,accessed 15 November 2010, http://www.civilwar.org/education/history/biographies/nathanial-lyon.html.

- Christopher Phillips, Damned Yankee:The Life of General Nathaniel Lyon, Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1990, pg 45.

- Nathaniel Lyon, The Last Political Writings of Gen. Nathaniel Lyon: with a sketch of his life and military services, New York: Rudd & Carleton, 1861, pg 26.

- Phillips, 83.

- Lawrence O. Christensen, William E. Foley, Gary R. Kremer, and Kenneth H. Winn, Dictionary of Missouri Biography, Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1999, pg 510.

- Phillips, 183.

- William Earl Parrish, History of Missouri: 1860-1875, Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2001, pg 13.

- “Nathaniel Lyon.” Encyclopædia Britannica. 2010. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 16 Nov. 2010 http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/352964/Nathaniel-Lyon.

- Parrish, 22.

- MISSOURI IN THE CIVIL WAR, Vol. 9, Chapter V, Confederate Military History, updated 2 February 2002, accessed 17 November 2010, http://www.civilwarhome.com/missouri5.html.

- Phillips, Preface xiii.